This paper presupposes knowledge of three components of external scale economies (agglomeration economies) as an urbanization force. The components are: labor pooling, access to specialized inputs, and knowledge spillover. Labor pooling refers to the co-location of firms and workers lowering the volatility for both sides of the market. Having many firms in the same industry means workers are less exposed to firm-side shocks. If your employer fires you because they are not doing well, you can relatively easily find another employer in the same industry. Similarly, co-located firms experience less volatility of labor supply, making it cheaper to hire labor in times of expansion than without co-location. So workers are insuring the firms and firms are insuring the workers. Access to specialized inputs refers to having high mean levels of a specialized input, such as capital or a natural resource. Knowledge spillovers refers to the sharing of knowledge in informal channels facilitated by proximity, such as unexpected conversations in a coffee shop or at the bar.

One of the notable characteristics of Renaissance Florence is the flourishing of art and architecture, collectively referred to as “art” in this paper due to the similarity in their consumption patterns. The Renaissance period is commonly cited as starting from around the year 1400 until the 1530s. As has been extensively studied, the clustering of art in Florence occurred due to a developed patronage system that connected wealthy Florentine guilds and families with artists. This paper reimagines a well-known narrative of the development of the Florentine art cluster with an urban economics lens. The discussion centers on patronage being an important specialized input to art that arose in the early 1400s due to changes in the forms of conspicuous consumption as the elites migrated from the countryside to the city. Labor pooling in the form of a wide distribution of patrons provided insurance for artists against patron retaliation, and training of artists as goldsmiths—a form of spinoffs—along with patron pressure to differentiate words combined with the artistic desire for freedom sustained artistic innovation in Florence’s art cluster throughout the 15th century. Social tensions in the late 15th century and threat of a foreign invasion in the 16th century disturbed agglomeration forces, lowering the intensity of the cluster.

Most stories about the rise of industrial clustering focus on modern cities which have large populations. Renaissance Florence is a pre-modern city which has lower mobility of goods and people, and low population levels with relatively low population density. One reason clustering occurs in large cities is because with a large population, there is greater potential for an individual to come up with innovation that begets clustering. Similarly, a greater level of economic activity makes innovation easier. Renaissance Florence provides a study of how agglomeration economies shaped a cluster in a pre-modern city.

At the beginning of the 15th century, Florence had a population of around 70,000 people. The largest city in Europe at that time was Paris with a population of 280,000 while Milan and Venice both had a population of around 125,000. By modern standards, 1400 cities were small and not particularly urbanized, limiting the potential clustering. The urbanization rate in Center-North Italy in 1400 was only 17.6%. At the same time, Italy was a lot more urbanized than other European locations. An average European urbanization rate in 1300 was 9.5 while urbanization rates in Center-North Italy were almost 20 percent with only regions like Flanders, Brabant and Holland having urbanization rates similar to Italy. In terms of urban structure, Florence had no central business district (CBD) and few if any local public goods (LPGs) existed with most of the government’s budget going to defense and interest payments on bonds.

Florence was one of the wealthiest cities in Europe around the start of the Renaissance. Its banking and wool industries were the main drivers of its wealth. The Florentine banking industry started its international expansion by collecting papal revenue in England and supporting the papacy in its opposition to the heirs of imperial Ghibellinism (aligned with the Holy Roman Empire) in the mid-late 13th century. Florentine bankers then served the papacy “in the international transfer of funds and exchange banking after its move to Avignon in 1305,” with the Alberti family being the most prominent banking supporters of the papacy. Integration into the papacy’s network allowed Florentine bankers to create an extensive network of European connections facilitated by Avignon’s location which ensured low transportation costs for the banking industry: “Avignon became a major node in the Florentine network… the city had a key position on trade routes extending northward along the Rhône valley to central France and the Low Countries, westward to Montpellier and Spain, and southward into the western Mediterranean commercial system.” The wool industry similarly prospered based on Florence’s international connections. High quality wool was imported from Northern Europe, especially England, and combined with dyes from the East, minimizing transportation costs of the two specialized inputs given Florence’s location in center-north Italy. Finished high-quality cloth was then sold to Near Eastern and Mediterranean markets. Both of these industries raised Florence’s wealth, and as a result made the Florentine florin a widely used European reserve currency with Florence becoming the place where rates of exchange for the currencies of Europe were fixed. The strength of the economy is summarized by the fact that “the revenue of the [Florentine] government in 1400 was greater than that of England in the heyday of Elizabeth.”

At the same time as the Florentine economy grew in the late 1300s, Florence was involved in many conflicts. Florence waged war against the Avignon papacy in the War of the Eight Saints (1375-1378). Then, the Ciompi Revolt happened in 1378 in which laborers took control of the government and Florence was governed by the Ciompi until 1382. “Beginning in 1389, Gian Galeazzo Visconti of Milan expanded his dominion into the Veneto, Piedmont, Emilia and Tuscany. During this period Florence, under the leadership of Maso degli Albizzi and Niccolò da Uzzano was involved in three wars with Milan (1390–92, 1397–98, 1400–02)” which ended with Gian Galeazzo’s death from a plague in 1402. Florence then incorporated Pisa into its land holdings in 1406, giving Florence access to the sea. The beginning of the 15th century marked a decline in feudal warfare and a start of a largely uninterrupted peace, opening up the doors to the urban forces that eventually resulted in what is now known as Renaissance Florence.

With the rise of peace in the early 1400s, Florence began to focus on its internal affairs. While the wars in the late 1300s were still ongoing, Florence was undergoing substantial changes. As mentioned before, the urbanization rate in Center-North Italy in 1400 was around 17.6% and many cities in that region of Italy have been highly urbanized for that time since the 1300s. However, the role of the city was constrained by constant warfare between the Italian city-states. As historian Richard Goldthwaite explores in his article The Empire of Things: Consumer Demand in Renaissance Florence, the early 1400s embodied the transition from a culture of feudalism which focused on rural land to a city-oriented culture. Under traditional feudal values—still dominant in most parts of Europe in 1400, especially the north—the elites asserted their status through large palaces and villas, a military ethos, and land interests. Feudalism called for traditional values embodied in the chivalric code. The elites trained in arms and expressed hospitality through welcoming guests in their large houses. Goldthwaite elaborates: “Consumption was directed to the rounding out of this scenario [of hospitality] for the assertion of status. Clothes, plate for the table, and retinues of liveried servants, dependents, and clients dominated expenditures… For this way of life, conspicuous consumption was a kind of investment in the noble’s social position that secured service and paid dividends in the universal recognition of his dignity and status” (emphasis mine). As coined by Thorstein Veblen, conspicuous consumption involved wealthy individuals consuming valuable goods with the primary goal being not the utility from the good itself, but the acquisition of status from consuming the good.

The relatively high level of urbanization of Italian cities—in contrast to northern Europe—resulted in an environment where cities resisted feudal-style assertions of status. Goldthwaite notes: “As a sense of public authority gradually asserted itself against the amorphous corporatism of the earlier commune, the nobility found its room for independent behaviour more constricted and its idiosyncratic ways curbed; and it eventually lost what had been its unique contribution to the commune with the increasing recourse to professional soldiers in the fourteenth century.” Even serving on the Signoria, the highest government office in Florence, did not allow for displays of status and terms of office were only two months. The lack of occasions for hospitality meant that a man’s status was not to be judged by the number of his attendants and the scale of his hospitality, and servants and a kitchen were not a major part of household expenditure. Goldthwaite again: “Feudalism provided the only real secular model for luxury expenditures, but it was an expression of values and attitudes that were remote from the realities of Renaissance Italy.” In short, wealthy households had no traditional way of asserting their status.

In response—as a way of asserting their status—wealthy households became art patrons. The wealthy sponsored architectural developments throughout Florence and such developments physically embodied their power and wealth. Similar to the feudal nobility’s investment in their social status through hosting guests, wealthy families’ of Florence conspicuous consumption of patronage asserted their status. In other words, the Florentine elite consumed not art, but patronage—art’s sponsorship. The rise of the city and the corresponding decline in traditional feudal values created a vital specialized input of art production—high levels of patronage from wealthy families. Peaceful times following decades of war meant that the wealthy could now focus on enhancing their status instead of worrying about potential disruptions due to ongoing conflict, with Florence’s and Italian urban structure pushing the wealthy to become art patrons.

Similar to individual patrons, Florentine guilds also became art sponsors. Florentine guilds were divided into seven greater guilds known as arti maggiori and fourteen minor trades guilds that were the arti minori. The guilds, especially the greater ones which included the wool guild, were wealthy as a result of Florence’s strong economy. Competition for political influence, with a similar idea of conspicuous consumption done by individuals, induced these guilds to commission high-quality art works to promote their reputations. As economist Tyler Cowen notes, “the commercial guilds exercised their greatest influence on large-scale sculpture, a medium that few private individuals could afford.” Arguably the most famous competitions occurred in 1401 when the cloth guild, the Calimala, commissioned the Baptistery bronze doors and Lorenzo Ghiberti got the commission by defeating Filippo Brunelleschi. Goldthwaite notes: “For half a century, from the 1401 competition for its second doors almost to the time of his death, Ghiberti was employed virtually full time on the two sets of doors,” highlighting the scale of funding necessary to support such a large project. “At Orsanmichele [church] another ambitious sculptural program got underway with the legislation for 1406 instructing the guilds to contribute statues of their patron saints for their respective places around the outer facades; by 1427 fourteen more life-size figures in stone were completed. The richest guilds—the Calimala ([cloth]), the Cambio (bankers), and the Lana (wool)—decided, in competition with one another, to pay ten times the cost of a marble figure to have their in bronze; so Ghiberti had yet another occasion to demonstrate his virtuosity, making the largest figures cast in bronze since late antiquity.” Another large commission occurred in 1418 when the wool guild—the Lana—announced a competition for the cupola of Florence’s Cathedral in which Brunelleschi won the commission over Ghiberti. Work on the dome began in 1420 and finished in 1436. Among other notable commissions, the guild of the armorers and sword makers commissioned Donatello’s St George around 1415 and the linen guild commissioned Fra Angelico to paint a Madonna for their guildhall.” Thus, conspicuous consumption as an assertion of status was an important force for both individuals and guilds. The specialized input of patronage ensured the high availability of funding for artists and started the art cluster of Renaissance Florence.

While the Florentine art cluster arose from the specialized input of patronage, the cluster was sustained through the forces of labor pooling and formal training—similar to Steven Klepper’s discussion of spinoffs within the contexts of Silicon Valley and Detroit—and contributed towards artistic freedom and a market that pushed artists towards innovations in the field of art.

Two key components of labor pooling within the context of Renaissance Florence include a relatively high degree of social mobility and a wide distribution of wealth providing artists with insurance against patron retaliation. If a patron stops supporting an artist because the patron lost confidence in the artist's potential, that artist can find a different patron as long as the artist did not engage in corruption or other undesirable behavior. If, on the other hand, the patron stops supporting an artist because of a negative economic shock, that artist could relatively find another patron due to the nature of Florentine social mobility. Goldthwaite notes: “The commercial-banking sector had ups and downs that could dramatically make and break fortunes. This sector was oriented to speculation in markets abroad and was not at all protected by a state banking system at home holding in the reins of money and credit, and men with investments in it were exposed to the unlimited liability of the partnership contract underlying business organization.” In other words, demand for patronage varied idiosyncratically—some families experienced negative economic shocks and demanded less patronage while other families were on the rise and engaged in more conspicuous consumption, lowering the volatility of artist earnings.

The wide distribution of wealth is best captured by the Florentine Catasto (tax assessment) of 1427, made in response to a high level of government debt as a result of an ongoing conflict with Milan that was expensive but ultimately not existential. “One-quarter of the total wealth of the city was in the hands of 100 men (heads of households), and one-half of the liquid wealth—commercial and industrial capital and credits—was in the hand of 250 to 300 men (2.5 to 3 percent of all those filing declarations). At this point, most historians end their exploration of the Catasto. However, Goldthwaite compares 1427 Florence to 1500 Nuremberg, one of the wealthiest cities north of the Alps which was half the size of Florence at the time of the Catasto. Comparing the top 100 assessments in both cities, he notes that in Nuremberg, 37 merchants were assessed from 10,000 to 100,000 Rheingulden (worth at the time about one-quarter less than the same amount of florins [i.e. 7,500 Rheingulden is equivalent to 10,000 florins], and the 63 others fall into a bracket ranging from 10,000 down to 1,000 Rheingulden; on the Florentine list of the highest 600 assessments, 86 men fall in the top bracket extending upward from 10,000 florins to 116,000 florins (not a very different distribution from that in Nuremberg, considering the population difference), and the second bracket containing all the rest has a cut-off point of about 1,500 florins. In other words, at the top level of wealth the Nuremberg merchants could almost hold their own with the Florentines, but at the next level the Florentines outnumbered them well over nine times.”

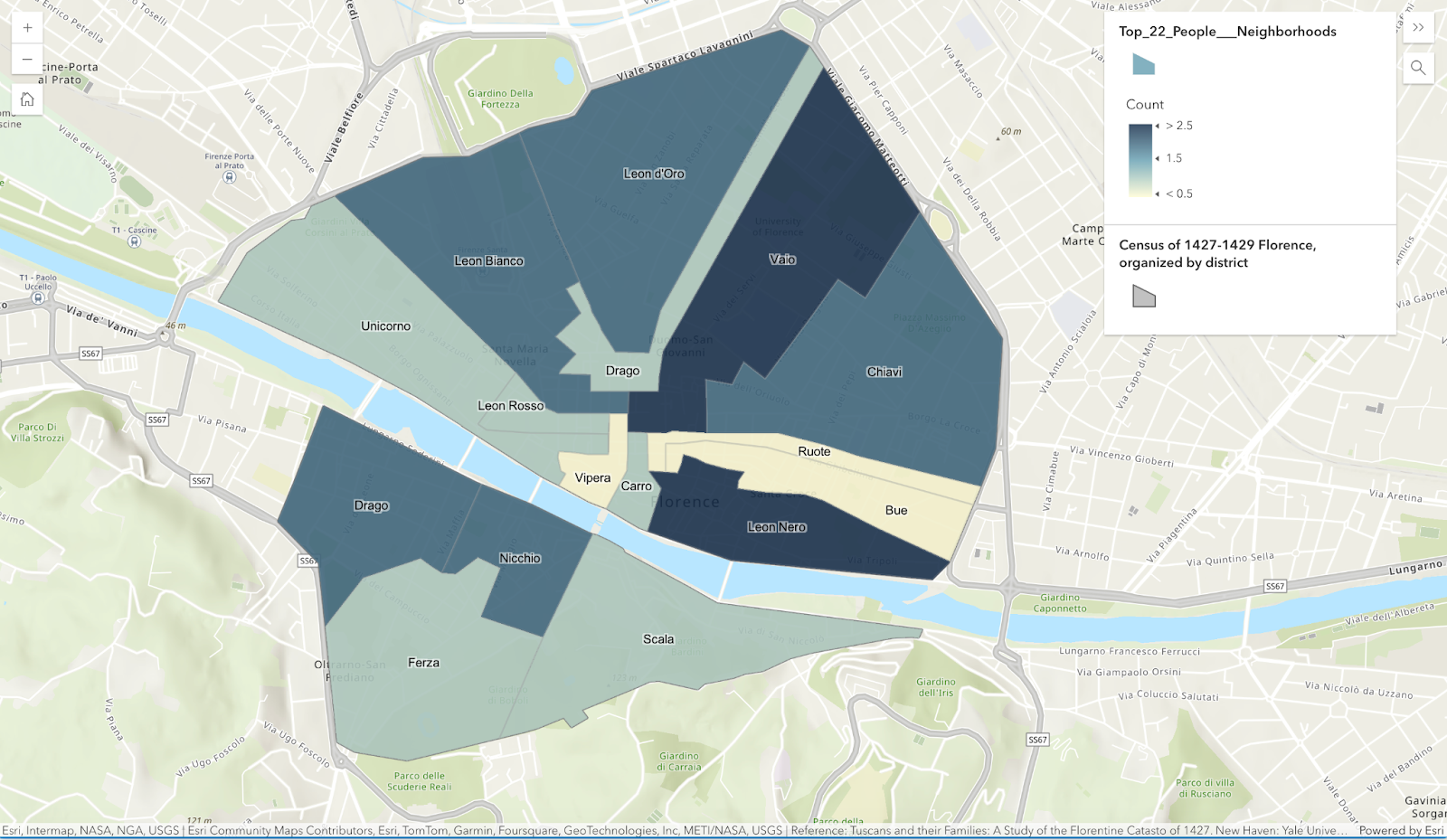

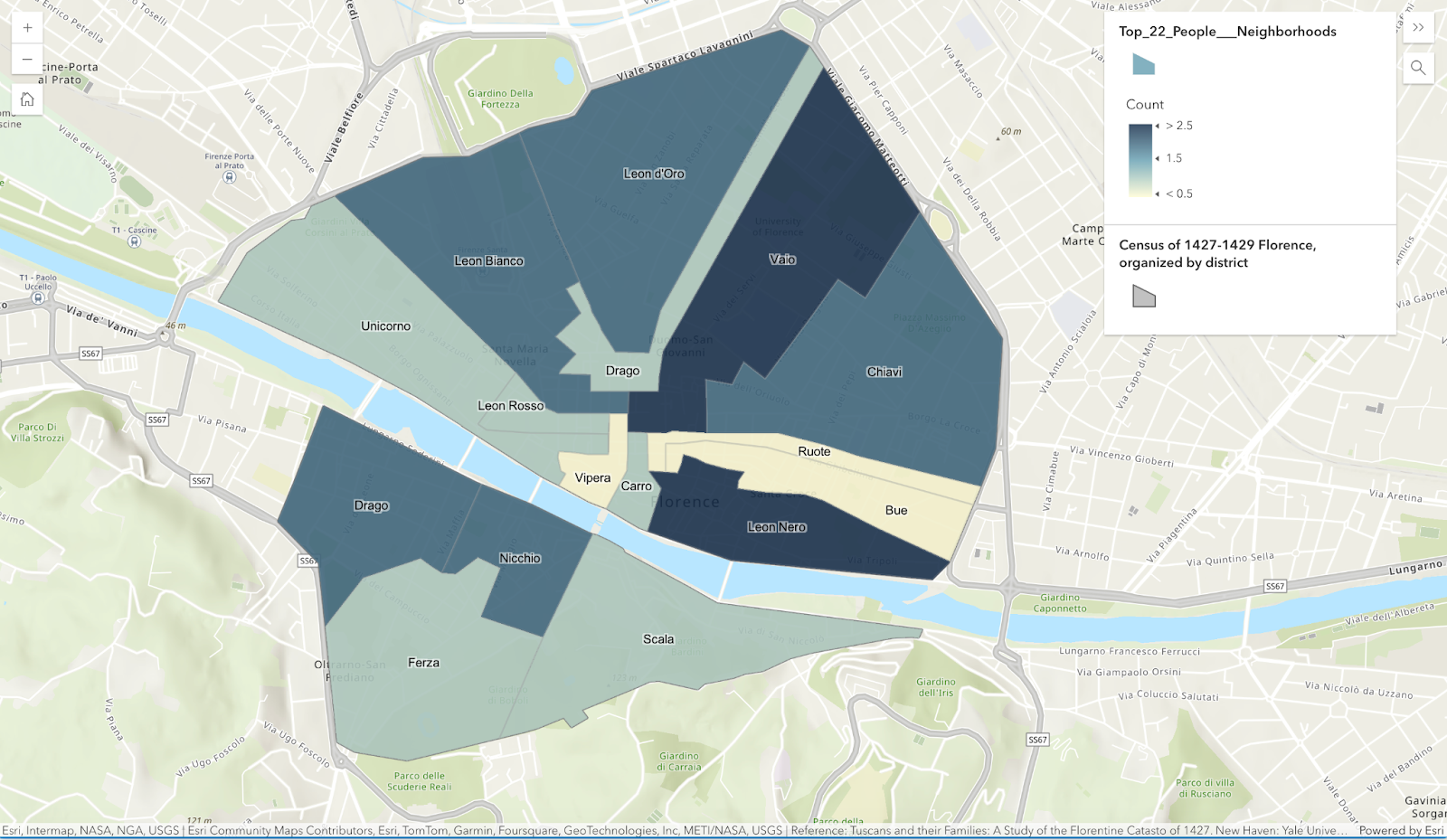

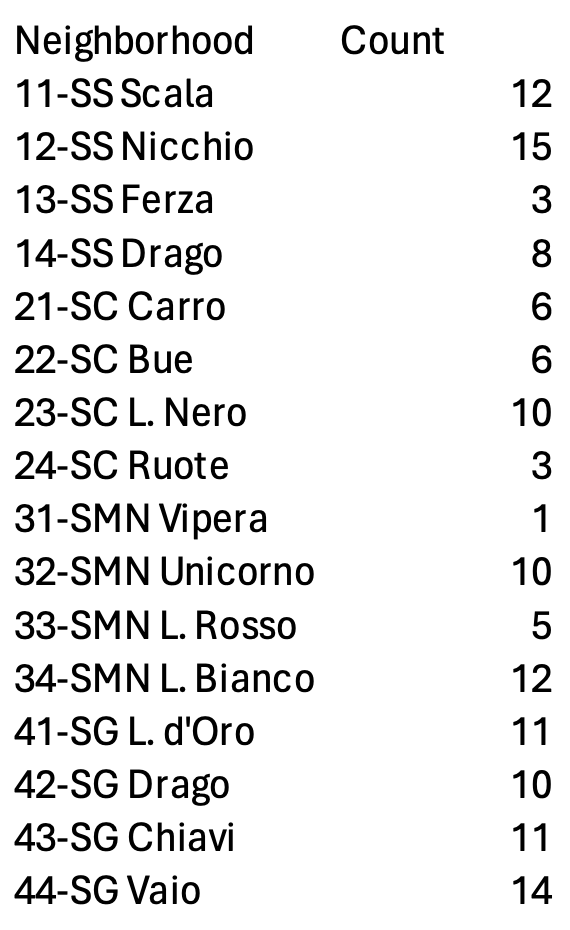

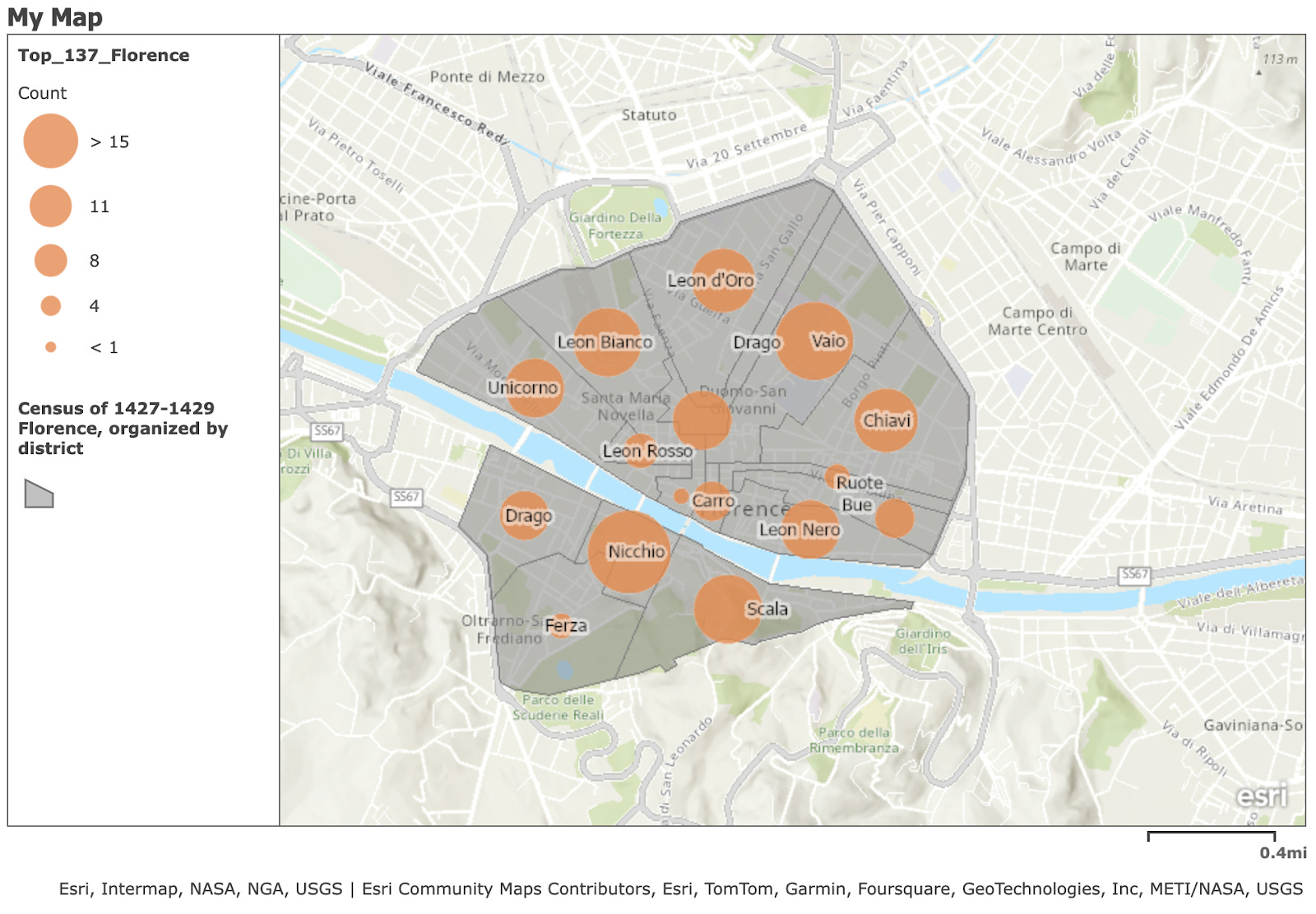

In addition, historian Gene Bruckner notes that the spatial distribution of families was such that wealthy families were not concentrated in any single part of Florence. Districts were heterogeneous and no sections of the city “were reserved exclusively for the rich, no ghettoes inhabited solely by the poor.” The observation makes sense from an urban perspective as Florence had no centralization force of a CBD nor amenities in terms of LPGs. “Each prominent family was closely identified with a particular neighborhood, where the first urban generation had settled—its members banding together for protection—in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. By 1400, the danger of physical attack from a rival house or faction was less real, but the pressures to remain in the ancestral neighborhood were very strong. For in its own district, a family could muster the support among relatives, dependents, and friends which enhanced its political role in the commune.” Based on the Catasto of 1527, when looking at twenty-two richest individuals (those with assets greater than 30,000 florins), only three out of sixteen Florentine neighborhoods have no representation on the list, six neighborhoods have one person on the list, five neighborhoods have two people, and two neighborhoods have three of the twenty-two richest individuals, highlighting the lack of concentration of wealth (Figure 1). Looking at the list of 137 households with at least 10,000 florins of assets, we see that the decentralization of wealth around Florence holds beyond the richest households in Florence (Figures 2 and 3). The wide distribution of wealth both in absolute and spatial terms made Florence an attractive place for artists. The high level of wealth provided the specialized input that jump-started the Renaissance and wealth’s broad distribution ensured the stability of artist funding sources over time. Simultaneously, the identification of patrons with a particular neighborhood made patronage even more attractive from a social status perspective. People of Florence know where prominent families live and that each of them values its neighborhood. Sponsoring art in the patron’s own neighborhood becomes the ultimate form of conspicuous consumption. Not only can patrons actively brag about sponsoring great artists, but people passively learn about the sponsorship in the course of their daily lives as they wander around different neighborhoods. Florence’s urban structure of patrons distributed across many neighborhoods created an environment for intense competition between patrons for funding the best art.

The reality of Florence’s art funding stands in stark contrast to other European and Italian cities which centralized artist funding in either the head of the state or the church. Historian Peter Burke provides the following description of what being an artist in other cities looked like: “Permanent service at court gave the artist a relatively high status, without the social taint of shop-keeping. It also meant relative economic security: board and lodging and presents of clothes, money and land. When the prince died, however, the artist might lose everything. When the duke of Florence, Alessandro de’Medici, was murdered in 1537, Giorgio Vasari, who had been in the duke’s service, found his hopes ‘blown away by a puff of wind’ [and Florence by 1537 was a court-dominated art city]. Another disadvantage of the system was its servitude. At the court of Mantua, Mantegna had to ask permission to travel or to accept outside commissions. It was not possible to avoid the demands of patrons as easily as those of temporary clients.” “An impression remains that court artists were more likely than others to have to dissipate their energies on the transient and the trivial.” “When an artist kept a shop, on the other hand, he had less economic security and a lower social status, but it was easier for him to evade a commission that he did not want, as Giovanni Bellini seems to have done in the case of a request from Isabella d’Este [of Mantua, a prominent patron of the Renaissance].” While permanent service provided artists with security, it made artists dependent on the will of the patron and fluctuations in patron economic status directly affected the artist whether through less funding for their work or a complete loss of their job. Naples, Milan, Ferrara, and Mantua centralized artistic commissions in the hands of the state. “Milan was much larger than Florence and possessed more military power, but its arts did not benefit accordingly. Milan did not have a comparably diversified background in commercial crafts [to be discussed in the formal training section]. Milanese culture was based around a princely court, especially during the reign of the Sforza family [1450-1535].” Venice was the most similar city to Florence in its financing of art due to its wealth which came from its trade ties with Orient, and the similar status of its ducat to the florin as a European reserve currency. However, Venice specialized in glasswork and mosaic, thereby not competing directly with Florence in architecture. There was some competition between Florence and Venice in painting, but that occurred closer to the end of the 15th century. In short, no Italian city offered the same high level of funding for art distributed across many patrons as Florence.

Another strong force for sustaining Florence’s dominance in the art world was its strong culture of formal training. Most successful artists went through an apprenticeship with another successful artist, a form of spinoffs that sustain the art clustering. Most of the Florentine artists were trained in goldsmithing. As Cowen explains: “Goldsmiths worked with a variety of forms, including gold, silver, bronze, marble, wood, clay, and textiles. Many of the objects made by goldsmiths, such as shrines and reliquaries, took on architectural forms and required drawing and design ability. Goldsmiths also acquired expertise in casting metals, setting jewels, and engraving. Sometimes goldsmiths were required to paint inlays on the pieces they set. They also studied the use of color and had a strong working knowledge of geometry. These skills accounted for the versatility of the Renaissance artist. Cowen adds: “The goldsmith and metal-working trades, prominent in Florence, supported and trained many artistic talents of the Italian Renaissance. In the Renaissance, Florentine wealth led to a favorable balance of payments on the gold florin and a continual inflow of gold. Goldsmithing activity was prevalent, and by the middle of the fourteenth century, forty-four goldsmiths’ shops lined the Ponte Vecchio… Many Florentine artists started out as goldsmiths or studied with goldsmiths to acquire the necessary technical skills. The list includes Orcagna, Andrea Pisano, Ghiberti, Brunelleschi, Donatello, Michelozzo, Luca della Robbia, Cellini, Antonio Pollaiuolo, Verrocchio (Donatello’s student), Leonardo (Verrocchio’s student), Ghirlandaio (Michelangelo’s teacher), Botticelli Andrea del Sarto, and Vasari. If we include those who studied with a goldsmith (Michelangelo) or whose father was a goldsmith (Raphael), we nearly exhaust the roster of prominent Florentine artists” (additional details about student status added in parentheses). Formal training of artists contributed to the cultivation of local talent. “Thriving markets for small artistic commissions and crafts were essential for training and supporting budding artists.” “For painters and sculptors, the fundamental unit was the workshop, the bottega - a small group of men producing a wide variety of objects in collaboration and a great contrast to the specialist, individualist artist of modern times.” This discussion points to the dominant role of the cultivation of domestic talent in Florence over the importation of talent from other Italian regions and from abroad as the dominant way in which Florentine artists rose to prominence. It also points to the difference between art and architecture within the context of Renaissance Florence. While architecture was primarily funded by patrons at first because of its degree of public display and magnificence, the broad training of artists meant that artists also ventured into art, but because of the smaller magnitude of an individual art piece, they are less historically discussed. In a study of six hundred painters, sculptors, architects, humanists, writers, ‘composers’ and ‘scientists,’ historian Peter Burke finds that 26 percent of the art elite came from Tuscany (where Florence is located) with its 10 percent share of the population. We can see that Tuscany is overrepresented in elite artists compared to its population. The value of visual arts is also apparent: 60 percent of Burke’s Tuscany sample went into the arts (95 visual artists to 62 non-visual artists).

While each of the previously discussed components of the Florentine arts cluster is important individually, their combination produced a magical outcome. High levels and wide distribution of wealth created an environment where artists could cluster in one location and not be dependent on a single patron for their livelihood. Competition between patrons in the creation of new architectural objects resulted in innovation in architectural methods. As Goldthwaite notes, “zeal for building sometimes inspires new ideas about architecture, especially when new buildings are being put up to establish the public presence of important men and institutions, whether merchants and monastic orders in Florence or banks and corporations in New York City, rather than to satisfy mere functional needs. When this is the spirit in which building is initiated, any innovation in style is likely to generate its own demand. Modernization for its own sake thus becomes a factor in the complex formula explaining the forces that converge in the marketplace to get new buildings built.” Artists had more freedom to experiment because of the decentralized nature of financing and, especially within paintings, less cultural church oversight during the Western Schism and the special relationship the papacy had with Florentine bankers. Unlike other Italian cities, the economic and urban structure of Florence encouraged innovation within the arts. Florence’s urban structure created a self-fulfilling flywheel of art creation unlike anything else in the world of Renaissance Florence.

Burke notes that a “characteristic generally ascribed to the culture of Renaissance Italy, and discussed in detail in Burckhardt’s famous book on the subject, is ‘individualism.’ Like ‘realism’, ‘individualism’ is a term which has come to bear too many meanings. It will be used here to refer to the fact that works of art in this period (unlike the Middle Ages) were made in a personal style… The testimony of contemporary artists suggests that, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, artists and public alike were interested in individual styles. In his craftsman’s handbook, Cennino Cennini advised painters ‘to find a good style which is right for you’. In his discussion of the perfect courtier and his understanding of the arts, Baldassare Castiglione suggested that Mantegna, Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo and Giorgione were each perfect ‘in his own style’... There was, of course, much imitation of classical and modern artists and writers. Indeed, it was probably the norm. The point about individualism, like secularism, is not that it was dominant, but that it was relatively new, and that it distinguishes the Renaissance from the Middle Ages.” At the end of the Patrons and Clients chapter, Burke concludes that Florence’s market “may well have encouraged the increasing differentiation of subject matter and individualism of style noted in the first chapter: the exploitation of the artist’s unique qualities in order to catch the eye of a purchaser.” Florence’s urban structure pushed artists to create art that differed from art produced in other locations. Florence’s cluster produced a unique type of art at the time of its flourishing.

Another insight into the Florentine cluster comes from the venture capitalist Paul Graham who notes: “It's in fields like the arts or writing or technology that the larger environment matters. In these the best practitioners aren't conveniently collected in a few top university departments and research labs — partly because talent is harder to judge, and partly because people pay for these things, so one doesn't need to rely on teaching or research funding to support oneself. It's in these more chaotic fields that it helps most to be in a great city: you need the encouragement of feeling that people around you care about the kind of work you do, and since you have to find peers for yourself, you need the much larger intake mechanism of a great city.” While Graham focused on the perspective of the artist, we can apply his insight to identification of artists in Renaissance Florence. An artist with a similar potential to Leonardo da Vinci could have been born in Milan in 1452. However, the Sforza family might not have misjudged the artist’s talent and refused to fund them. Theoretically, the artist could have moved to Florence and become an apprentice, but the artist is not part of the Florentine network and is unsure whether they’ll be able to find a job. The artist’s family and friends are all located in Milan and the prospect of moving to a new city without any network or support would be an incredibly high risk endeavor. Risk taking outside of an established cluster has high costs. In Florence, on the other hand, all the patrons would be competing for sponsoring the up-and-coming artists. Even if the most famous patrons of that time, the Medici family, refused to sponsor that artist, other patrons would be on the lookout for them and given signals of the artist’s inclination towards greatness, would become their sponsor and gain status in the process as the discoverers of great talent. Florence’s urban structure helped great artists get discovered as every patron competed in the arena of maximizing their prestige by sponsoring great art. The Florentine cluster, dictated by its urban structure, developed up-and-coming native-born artists who then produced art of a distinct kind.

The Florentine cluster began its decline towards the late 1400s. The event that truly marked the decline was the rise of Girolamo Savonarola, a preacher who seized power in 1494 and imposed restrictions on art, literature, thought and behavior. In other words, Savoranola restricted conspicuous consumption. Seeing how much the wealthy spend on patronage, “Savonarola scolded these builders because he could not get them to give 10 florins to the poor, whereas if he asked them to pay 100 florins for a chapel in San Marco they would do it just to display their family arms.” Savoranola was executed in 1498 and art-friendly rules in the face of the Medicis came back to power, but that display disrupted the art cluster.

Around the same time, Pisa took advantage of the French invasion and declared its independence in 1494. In 1497, Florence embarked on a war with Pisa, but the endeavour failed miserably, and this led to food shortages. The Florentine Republic was in decline. The state of the city that was unfriendly towards patronage and had a food shortage decreased the value of specialized inputs and labor pooling. By that time, Venice moved towards a market system for art and was competing with Florence in the realm of painting, lowering the strength of Florence’s art cluster. Some of the most prominent artists who were at least trained—if not raised—in Florence, such as Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael, went to work in Rome for the papacy as both Julius II (1503-1513) and Leo X (1513-1521) sought to increase the papacy’s prestige by spending money on expensive art commissions.

Florence was under siege for 10 months in 1529-1530 by the Spanish. “Threat of Spanish rule centralized Medici authority” and “political centralization (in 1531) brought true Medici dominance over Florentine art. By mid-century Cosimo I ruled Florence with an iron hand and centralized the finance of Florentine art in his office” “Cosimo I did not stop at funding his own projects but also restricted competing sources of patronage from friars, guilds, confraternities, and families. Rights of private patronage over chapels were canceled and artistic commissions were now subject to central regulation.” The centralization of patronage ultimately nullified all the benefits of access to the specialized input of patronage with its wide distribution, destroying the Florentine arts cluster.

Florence’s background in banking and wool created one of the richest economies in Europe in the late 13th century and early 14th century. The decline in traditional feudalist values displayed in rural areas and the switch towards a city-based method of asserting status resulted in wealthy families turning towards patronage as a form of conspicuous consumption. Rich guilds engaged in similar forms of conspicuous consumption. The very high level of Florentine wealth along with its broad neighborhood distribution meant that patrons competed intensely in sponsoring great art and artists were insured against retaliation from an individual patron. Artists were formally trained in goldsmithing and acquired a diverse array of skills. Florence’s type of patronage—a result of its urban structure—pushed artists towards innovations in the arts as both artists exercised their artistic freedom and patrons pushed artists towards innovation as a way to solidify their status.

As a pre-modern city, Florence had no centralizing forces beyond its jobs. By modern standards, Florence would be a small city. In spite of that, urbanization forces of agglomeration economies practically indistinguishable from the modern day created and sustained Florence’s art cluster. Florence created an environment where up-and-coming artists were discovered by patrons and trained by successful artists in formal apprenticeships. The Florentine art cluster encouraged and rewarded patrons for finding talented artists, giving them bragging rights and increasing their social status. The lack of competition for artists from other city-states made Florence’s cluster easier to sustain and Florence’s urban structure ensured both the discovery of new artistic talent and their continual involvement in the Florentine art cluster. The decline of public support for the arts, embodied in the ruling years of Savonarola disrupted the cluster with some of the best of Florence’s artists soon moving to Rome to work for the Pope. A looming war with Spain resulted in a centralization of power in the hands of Cosimo I de' Medici which put an end to Renaissance Florence through the destruction of the specialized input of a large amount of funding and the labor pooling benefits of insuring artists against retaliation by an individual patron.

Overall, Florentine art represented a radical departure from traditional art of that time. Ideas expressed by Florentine artists showed individuality and expressed creativity. Florence’s urban structure encouraged experimentation in the arts and experimentation is what gets recorded in human history, for history that is a continuation of the status quo loses in prominence to innovation. Florence’s urban structure produced artistic flourishing and its art entered humanity’s historical record.

Figure 1: Neighborhoods where 22 richest people in Florence lived. Data is based on the Florentine Catasto of 1527. Note: all pins are at a neighborhood level, not an address level.

At least 30,000 florins. Both Leon Nero and Vaio have 3 households with rich individuals.

Data: David Herlihy and Christiane Klapisch-Zuber, Census and Property Survey of Florentine Domains in the Province of Tuscany, 1427-1480. Machine readable data file. Online Catasto of 1427 Version 1.1. Online Florentine Renaissance Re sources: Brown University, Providence, R.I., 1996. https://cds.library.brown.edu/projects/catasto/newsearch/index.html.

Figure 2: Count of Top 137 that live in a given neighborhood.

Figure 3: Distribution of top 137 households by neighborhood.

Data: David Herlihy and Christiane Klapisch-Zuber, Census and Property Survey of Florentine Domains in the Province of Tuscany, 1427-1480. Machine readable data file. Online Catasto of 1427 Version 1.1. Online Florentine Renaissance Re sources: Brown University, Providence, R.I., 1996. https://cds.library.brown.edu/projects/catasto/newsearch/M1427g.html#14.

Note: The 137 households (1.4%) with 10,000 Florins or more of total assessment in 1427 by Gonfalone.